The Reform Movement around 1100

The Cistercians emerged in 1098 from the Cluniac monks as a Benedictine reform movement. The impetus was the intention to renew the Rule of St. Benedict, who had a formative influence on Western monasticism, in its original rigour. This was the basic idea behind Robert de Molesme's founding of the Cistercian monastery in 1098 in Cîteaux, Burgundy, the place that gave the new order its name.

There, in eremitic seclusion, the purity of the basic Benedictine formula "ora et labora" was to be reinterpreted and lived as an expression of a meaningful connection between prayer and physical work.

St Bernard of Clairvaux

Bernard of Clairvaux (1090/91–1153), who entered Citeaux in 1113 with 30 like-minded friends and relatives, very quickly became the defining protagonist of the newly founded order and, moreover, the leading figure of his time. As early as 1115, he took over the office of abbot in the newly established monastery of Clairvaux, from where he made a decisive contribution to the rise and spread of the Cistercian order. The reform monastery was transformed by him into an extraordinary centre that had a decisive influence on the religious and economic development of Europe. At the same time, he influenced the spiritual disputes of his time and intervened in political events, for example through his widely received crusade sermons. In 1136, at the request of the Archbishop of Mainz, he came to the Rheingau valley with 12 other monks from Clairvaux and founded the Eberbach abbey.

Even during Bernard's lifetime, the order numbered almost 350 Cistercians , and a century later, almost 650 abbeys. The principle of filiation, i.e. the founding of "daughter abbeys" when a sufficient number of monks was reached in the "mother abbeys", was decisive for the expansion. In the course of time, 355 monasteries were founded at Clairvaux alone, with Himmerod in the Eifel and Eberbach in the Rheingau the only remaining German branches of Clairvaux.

Settlement and Secularisation

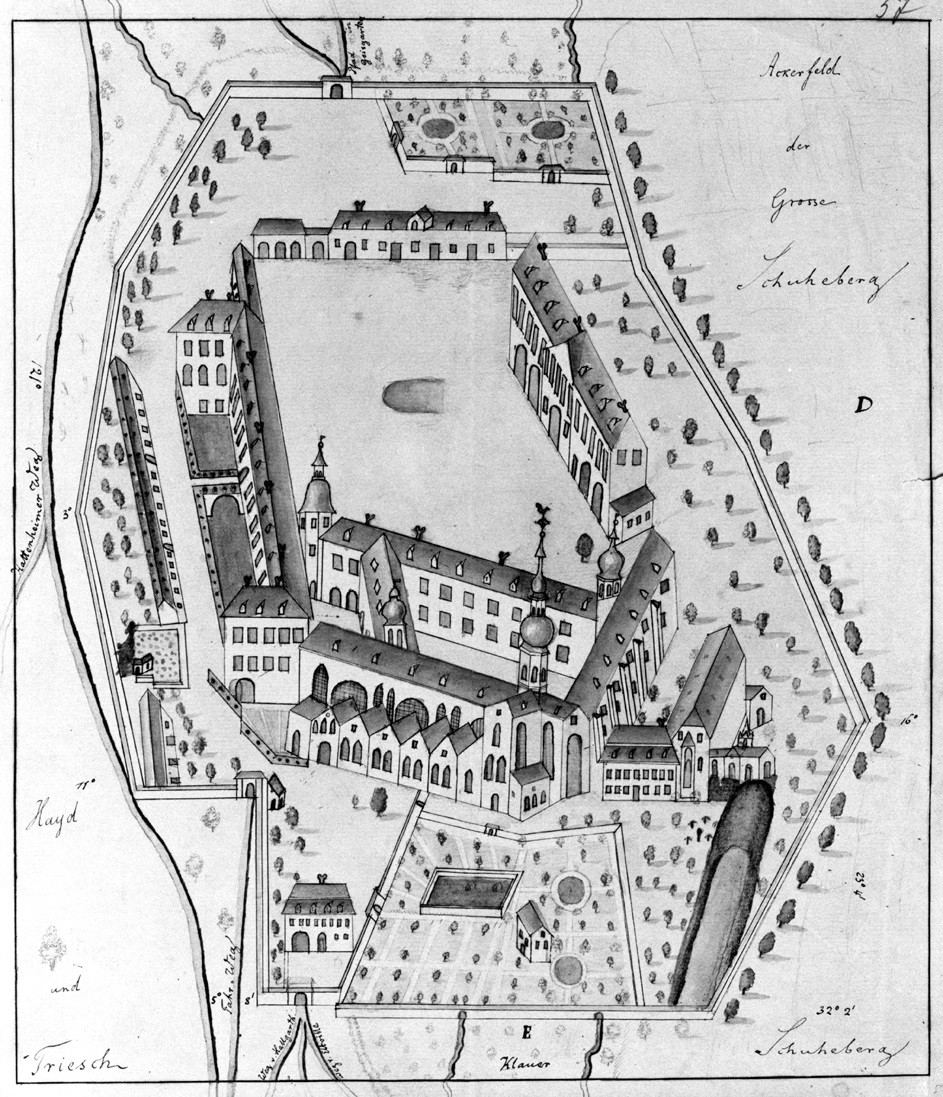

When selecting a site for the settlement of a new abbey, water-rich and secluded valleys were usually chosen. This was based, on the one hand, on the eremitical ideal of the reform order and, on the other hand, on the availability of constant fresh water for the operation of water pipes, mills or fish ponds. Additionally, there was usually a rich quarry in the vicinity of the sites chosen, which supplied the material for constructing the large structures, almost exclusively erected as solid buildings.

After a significant enlargement of the order in the 12th century, the expansion reached its limits in the 13th century in the course of the spread of the newly emerging mendicant orders. Later, monastic life increasingly deviated from the initial rigid conception of the Benedictine rules. In the 17th century, Kloster Eberbach was also influenced by the baroque style of monastic life typical of the time, which can still be seen today in some of the new buildings and conversions. Enlightenment thinking prepared the ground for the secularisation of many Cistercian monasteries, which were considered to have outlived their usefulness. This led to the abolition and often the demolition and dereliction of many abbeys in the wake of the French Revolution, both in its mother country and – under Napoleon's influence – in Germany. Since then, only Himmerod and Mariawald (Trappists) in the Eifel and Marienstatt in the Westerwald have been resettled by monks in Germany, while the number of Cistercian monasteries is much greater today.